Parallel Formations: Art as Mirror to Institution and Institution as Mirror to Art

In recent months, I have had the pleasure of working more closely with the Stedelijk Museum, the modern and contemporary art museum in Amsterdam. As I study and prepare to lead tours at this museum, two things strike me:

- I am so happy to be returning to some of my favorite art movements that I studied in university, and

- There is somewhat of a parallel between the evolution of art and the evolution of museums.

Jerry Saltz argues that art changes the world incrementally “by first changing how we see, and thereby how we remember”; however, I would argue that museums play a role in this world-changing characteristic as well.

Before I get started, I will point out that these trends are something that have lived in the back of my head for some time now, but I have to admit that the timing of the art and museum trends don’t always match up perfectly (despite studying Art History in university, I have always been terrible at dates). In some instances, it seems that the museum trend may have influenced the art movement and the reverse in other cases, although it would be a better bet, in my opinion, that the underlying societal, political, etc. forces coordinated both ends of these trends (both museum and art).

The Elite and the Cabinet of Curiosities

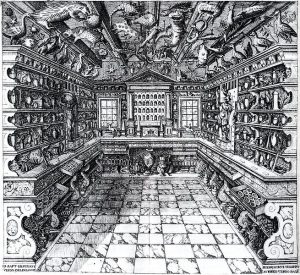

As far as museums in the Western world go, many museum historians argue that the cabinet of curiosity (aka wunderkammer) and/or the international fairs were precursors to the contemporary conception of the museum. Of course, back in the time of the cabinet of curiosity — during the Enlightenment —, an aristocratic and royal hierarchical structure to society still existed, which gives us a pretty solid backbone for understanding how these cabinets came about.

Although, of course, many cabinets of curiosity came about for different reason, they were all made for, by, to serve the elite. Many young men during this time, for example, would travel around Europe for a year or two to become more learned and cultured; many of these cabinets of curiosities would be displayed without information (no exhibition labels!) to help young men who were cultured and traveled learn and study great art and (white, male) artists.

This concept of the cabinet of curiosity clearly echoes the development of art at the time. Although much art was commissioned for religious purposes by the Catholic church, the rest mostly laid in the hands of the rich and the royal. Think of, for example, Vermeer’s array of interior paintings; although they seem to depict daily life, they certainly depict the daily life of the extraordinary rather than that of the average worker. This has also acted as a palimpsest for contemporary museums, whose collections from this era still largely reflect the daily extravagance of the elite rather than the material objects of the average person, whose belongings have long since perished.

Democratization of Art and Museum

With the conclusion of the French Revolution, the new government sought to turn the Louvre over to the people as quickly as possible. This Robin-Hood-like gesture symbolized the shift in power in 18th-century France: not only was the government now the property of the people, but so was the former royalty’s prized possessions.

Nearly a century later (let’s generously give the French some time to adjust to their new government), Impressionism splashed on to the scene as a marked alternative to the authoritative Salon. Daubigny, involved with the Salon as well as a sympathizer to the Impressionist movement, was able to help open the door for this new wave of artistic expression. By opening this door, the authority of the Salon was compromised and it rapidly lost its once-almighty status in the realm of art.

Art and Museum as Civilizing

Early 20th-century museums began to consider themselves as educators and civilizers of the public; by inviting the public into their halls, museologists believed that citizens could become more polite, cultured, and civilized. This is most popularly expounded upon by Carol Duncan, in her conception of the museum as a ritualistic space.

This is echoed in, for example, the architecture and design of the Amsterdam School movement. Buildings constructed by Amsterdam School architects such as Michel de Klerk were based upon socialist ideals; many of these buildings were constructed for the working class, government institutions, and schools. Furthermore, the goal was to create an architectural experience, by incorporating Amsterdam School furniture, the interior and exterior blended together seamlessly, and this inclusion of art and design in factory workers’, students’, and government employees’ lives was thought to improve their daily lives.

The Artist as Genius and Contemplation

Although the artist as genius is a persistent theme throughout the past several centuries of art history, I have a sincere hunch that van Gogh’s legacy, infamy, and notoriety has heightened this obsession with the artist as genius and has also added the idea of the suffering artist to this image.

Following with this, Abstract Expressionists — who often happened to be influenced by the works of van Gogh — relied heavily on the idea of the artist as genius as well as the affective and emotive experience of the artist. The thick impasto and chaotic brushstrokes of artists such as Willem de Kooning prompt viewers to consider the actions and intentions of the artist, indicating that the artist’s emotive experience or message is central to the interpretation and experience of the artwork.

Reflecting this, museums began to display these artworks with little to no context and on bare white walls, which provide space for clarity and contemplation (this also relates to the museum as a civilizing institution). The lack of historical and contextual information — although you could argue that paintings hung in the same room could provide some context — clearly encourages the thought that the artist and the art object are of ultimate importance.

Participatory Practices in Art and Museum

Artists and museums now seem to focus on the viewer and the visitor, respectively. We can think of an artist such as Felix Gonzalez-Torres, who often created works (e.g. Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.), 1991) that were created with viewer interaction in mind or of artists such as Krien Clevis who engage in artistic research interventions with the public.

On the museum end of things, we need only look to the overly cited work of Nina Simon and think back upon the call of John Cotton Data to focus more on the visitor and museum education to get an idea of the ideology behind participatory practices in the museum sector today.

However, these participatory practices don’t end here; I can’t speak for other fields, but the museum field abounds with conversations about social justice, feminism, (in)equality, and representation. Following along from the participatory practices cited above, these practices also hope to incorporate the public in an effort to demonstrate their inclusion of the diverse audiences and populations surrounding their institutions or practices.

Returning to Saltz’s article, he argues that this New York exhibition called “The Keeper” incorporates non-art art; in other words, art that would likely be rejected by the limiting sensibilities of art history. To me, it seems that art movements have always sought to reach the edges of art — when the Salon was in fashion, the Impressionists sought to express an urgency and emotiveness absent in Salon paintings; when photography seemed to outclass realistic paintings, artists turned to the paint as material; when World Wars turned the world upside-down, Dada sought to capture the essence of societal chaos and confusion — and museums are likewise chameleonic, although many would argue that they are much more slow-going in their metamorphoses — the Louvre museum was given to the people through the French Revolution, exerting the right of everyone to culture and art; museums are collecting “everyday” objects of furniture and design, confronting the definition of art; museums are exploring the possibility of transhistoricity and the fluidity of art historical periods and themes.

Many art historians and museum practitioners would argue that artists are typically on the cusp of change, riding the waves of history to new shores; my argument would be that the relationship between art and museum is integral, a mutual discursive conversation that is both girded by and reactionary to the complexity of the contemporary environment.

Perhaps by hailing Saltz’s call to restructure our conception of art history as a “garden”, by also further incorporating study of societal, political, and cultural structures that marginalize(d) certain artists and art movements while glorifying others, we can gain a better understanding of the (art) historical forces that brought certain artists and movements to the fore as well as nourish the long-neglected poppies and dandelions that so deserve a spot in the sun.

This post originally appeared on the Tangible Education blog.